Engineering class writes its own toy story

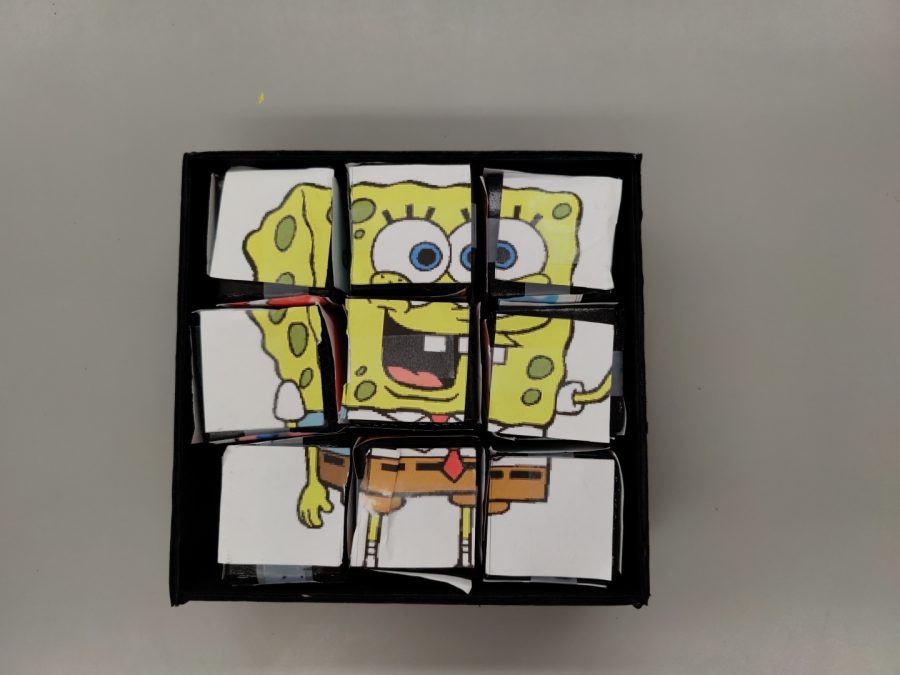

Six different pictures are cut into nine pieces and glued to each of nine blocks. The resulting puzzle challenges users to either solve the puzzle or use the blocks to build something.

February 9, 2022

What looked like child’s play in Vincent Komar’s classroom was actually serious business with real-world applications. The balls, marbles, rings, and strings were just some of the toys neatly lined up on the counters of Q 206, prototypes of what might one day be used by families and therapy clinics.

Three weeks ago, Komar challenged his Engineering Tech I students to design a toy that was developmentally appropriate for a child with cerebral palsy, a condition in which a person’s muscle development and coordination make moving difficult.

Students engaged in the design process by first researching cerebral palsy and then developing a toy that a child aged 3 to 7 years would find educational, therapeutic, and most importantly, fun.

After students had completed their own proposal, Komar put them into groups, and the groups had to decide which one of their designs had the best potential.

“They had to make presentations to each other and then look at the project criteria to pick one of their designs,” Komar said.

Last week, student groups began presenting their prototype toys to the class, explaining how they used engineering skills to complete the task. Classmates then provided feedback.

Sophomore Zuxing Zhen, sophomore Gage Tani, and senior Jayden Berano created a multi-functional toy that was a cross between Fisher Price and E. K. Fernandez Carnivals. The team designed a toy that addressed a patient’s fine and gross motor skills as well as appealed to sound and sight. Their invention encourages children to stack or toss colorful rings of different widths over a hollow base or try to toss the clear bags filled with rice (as opposed to beans) into the base. They could even toss the rice bags into the rings themselves, which could be laid on the floor.

“We put different amonuts of rice in the bags, so [children] can see and hear the rice moving and sounding different,” Tani explained to the class.

The different widths of the rings would challenge the user to change the finger grip while handling them.

Komar suggested afterwards that older children could toss the rings like a frisbee or flip them like horseshoes to practice different wrist movements.

Senior Marcus Gonzalez worked alone on a two-sided wood and plastic frame with a maze built inside, where children tilt the box to move a marble around. Gonzalez drilled holes in the four corners for added challenge. He explained to the class that he had three other ideas but “thought about the audience and the resources [he] had,” and settled on the maze.

“I’m proud I was able to make a functional prototype in the time I had,” he said.

Sophomores Patrick Baldovi, Nathan Luong and Caleb Nelson invented a toy that invites children to place balls into one of three chutes to see where it emerges, sort of like a mini golf game.

“It was fun getting hands-on experience with the design process,” Baldovi said. “We had to do a lot of research to find innovative ways to make our toy fun and helpful to people with cerebral palsy.”

Going through the design process opened students’ eyes to the necessity of rethinking and revising their projects.

“It was just fun to watch the evolution of the students over the three-and-a-half weeks, especially when it came to the design process,” Komar said. “In their minds, they had a clear idea of what they envisioned, but as they went through the process, they saw that it had to change.”

For example, students realized they were not able to obtain certain materials or that the design did not work as they expected or failed to meet the project criteria.

Komar said he was pleased that overall, the project encouraged his students to learn to function as a unit.

“Before, [the students] worked by themselves, but now they had to collaborate and work cohesively as a team,” Komar said.

Junior Dayson Hashimoto said he appreciated the collaboration aspect of the project.

“I enjoyed meeting new people and forming new bonds,” he said. “It was interesting to see how people interpreted the data.”

His group created an activity box that encouraged children to use different implements to pick up or move smaller objects from one place to another, similar to the “Operation” board game.