Black History Through Film

February 28, 2022

The history of black people in film is unfortunately much like the history of black people in American history. It is a constant uphill battle for an oppressed group of people, the fight for equality by those who have not had it and in many ways still do not.

The films that do represent black people can be a touchy subject; it is only appropriate and just that many black stories in film are not uplifting ones. But despite the hardships that black representation has faced in the film industry, both in front of and behind the camera, the undeniable triumphs should not be overlooked, and their cultural relevance will ring throughout time.

However, this story does not have a happy beginning. Turning back the clock to 1915, when cinema was still in its infancy, D. W. Griffith’s landmark film The Birth of a Nation was released to vast acclaim. Never before had a movie of that sheer size and scope been filmed at the time, and Griffith pioneered revolutionary filmmaking techniques that set the precedent for every movie filmed afterwards.

But the film also painted a blatantly racist picture of black people, a great deal of the film centering on the Ku Klux Klan and their persecutions of black people, involving lynching and unfair sentencing in courts. Black men, especially, are disgustingly depicted as savages, particularly in a scene where one black man tries to rape a white woman, which “forces” the woman to jump off of a cliff.

The fact that this film was so heavily revered at the time is a lot in part due to the bigoted mindset of America and especially Griffith, who is still cited as one, if not the best film director of his time. That and the return of the Ku Klux Klan stirred the public consciousness, a common theme throughout the history of cinema as a whole. Art often influences and condones behaviors, leading to justifications both good and bad.

For a long time, the justifications for racism were ever-present and unavoidable. One of the most infamous examples throughout early film history is in the 1927 film The Jazz Singer, where blackface, the act of white people putting on extensive make-up to imitate and mock black people, played a huge role.

Another example is with the 1939 “timeless classic” Gone With The Wind. The character of Mammy, played by Hattie McDaniel, is a nurse and maid for the main character, barely above a slave, who is also funny, feisty, and has the occasional smart remark, essentially romanticizing her repressed state (similar to the main character of Disney’s Song of the South, which they will never release to the public for the sole reason that it idealizes the life of a slave). This has since become a stereotype that persists even today, known as the “Mammy character,” who is most often a black woman who plays a supporting or background role in the story, providing sass and smart remarks, but is clearly there only for humor. The fact that McDaniel won an Academy Award for her performance, the first black person to ever win an Oscar, says everything you need to know.

Both The Jazz Singer and Gone with the Wind are not only some of the most influential films of their time, but of all time, and widely acclaimed by critics and audiences alike. The Jazz Singer was the very first “talkie,” which are movies that had characters talking instead of the film being a silent picture with dialogue cards. And Gone with the Wind, much like The Birth of a Nation, proved that filmmaking could be so much more than simple back and forth shots, and was also one of the first movies to utilize color in a truly stunning way, and as much as I dislike the film, I can’t fault it for looking absolutely gorgeous.

However the fact remains that these early movies, when films were still relatively new, were highly influential and will continue to be talked about for as long as people study cinema. And with that discussion, the racism against the black community will continue to live on, and it hauntingly captures the state of America at the time.

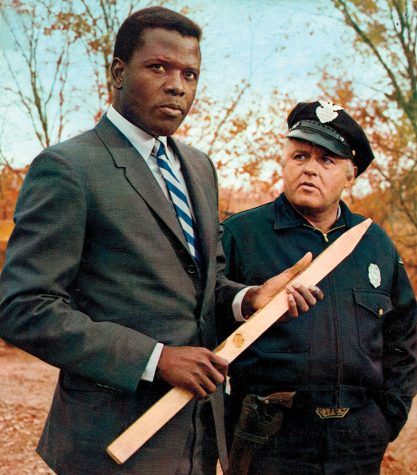

Directed by Norman Jewison

Shown from left: Sidney Poitier, Rod Steiger (United Artists/Photofest)

But mindsets improved as time went on, and films started to give more representation to the black community and their stories. A major catalyst for this, in the heat of the civil rights movement, was In the Heat of the Night, with perhaps the most influential black actor of all time, Sidney Poitier. Released in 1967, it was, and still is, considered trailblazing in its portrayal of race relations and prejudice.

The movie follows Sidney Poitier as the now-iconic detective Virgil Tibbs, who arrives in a Southern town to solve a murder. He has to work with the extremely bigoted police chief played by Rod Steiger, who has to grapple with the fact that he has to cooperate with a black man to bring peace to his home. A depiction of a black man on the silver screen had never been this show stopping before, and it was all through Sidney Poitier’s pitch-perfect performance, being level-headed and rarely losing his steam at every right moment. In a town where white people rule, the black man does all the right things.

Winning Best Picture at the Oscars cemented this film in the history books as a step in the right direction for the public consciousness to be more fair to the black community. In the following years, Sidney Poitier would be in a number of films that pushed boundaries, in particular the 1968 film Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?, one of the first movies to address interacial marriage in a positive light. From the 1970s onwards, black people were addressed with much more fairness and equality.

The 1970s were also a monumentally important decade for the black community, for good and bad reasons, because perhaps the most important film trend of the 1970s was the blaxploitation movement. Kickstarted by Melvin Van Peebles Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, the blaxploitation movement saw mass black representation through film, in both the acting and filmmaking departments.

This representation, however, did more bad than good for the black community. Even though black actors were getting prominent screen time and leading roles, a rarity before the 1970s, most of these roles were massive stereotypes that have persisted to this day. The black man was often depicted as a pimp, a drug dealer, a gangster, or some other lowlife that society is meant to look down upon.

While contemporary artists have worked to break down these stereotypes and tell more truthful stories about the black community, one decade’s worth of damage did its work for five. Despite all of the exposure that this gave black artists, as well as the grand amount of entertainment that all of these films provided, the problem of black stereotyping exists so strongly today in part thanks to these films, serving as validation for sick minds to twist public perception of everyday people.

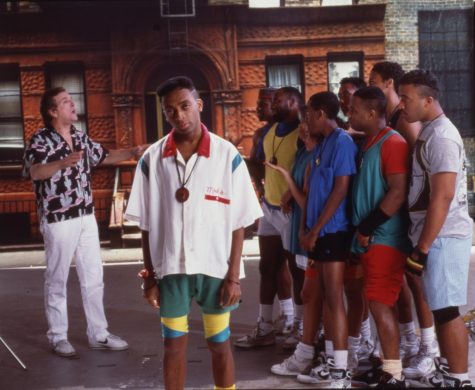

Throughout the late 1970s and 1980s, black people started getting fairer screen representation at least in some capacity, but a paradigm shift not just for film history, but in black history occurred in 1989 with the release of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing. The film was a revelation, no director had ever before so passionately displayed their message on the screen. It addressed ideas that many in society were too afraid to talk about, mainly how racism and prejudice was (and still is) a problem that should not be sweeped under the rug.

It wasn’t just the idea of racism being so commonplace that made this movie unlike any that came before, but it also depicted the harsh reality that prejudice, though it may be based on bias, is universal. Everyone is a victim of prejudice, and Spike Lee swaggeringly demonstrates this in the film’s best scene, where many of the main characters speak directly to the camera and hurl insults (many of which are racial) at each other. As stylized as Do the Right Thing is, it continues to be a harsh reflection of the real world, one that puts a microscope on a singular black community throughout a hot summer’s day. I personally can not wait for the day that this movie will not be relevant anymore.

Once Do the Right Thing was released, many more movies about black justice and racial inequality were produced and received greater exposure. Since 1989, black voices and stories have only become more commonplace, with a lot more black actors receiving leading roles in films. This continued to happen steadily all throughout the 1990s and into the 21st century, and more realistic and truthful stories of the black experience were being told in particular.

In 2013, 12 Years a Slave won critical acclaim for taking the real-life story of Solomon Northrup and conveying the visceral, harsh, and unforgiving experience of the cruelties of slavery and the hate that black people received during the mid-19th century.

Another landmark film was Moonlight (2016), which tells the story of a black boy growing up, experiencing love, and finding out who he really is. What was so special about Moonlight was its honesty and how it made for an emotional experience unlike any other. There is no sensationalization in Moonlight, only raw camerawork and conversations, paired with stunning visual imagery.

Here was a movie that didn’t treat the black community as anything to be idealized or overblown, but simply just as everyday people. And by doing so, Barry Jenkins was able to tell a story that was far more meaningful than it could have been, with universal themes about how the experiences and people we meet constantly shape our identity, and how masculinity and sexual stereotyping can be dangerous. Moonlight is an absolute masterpiece and one of the best movies ever made, and an essential part of film history, especially black history through film.

As of today, multiple movies per year are released that not only comment on the black experience, but serve to empower their community, the biggest one being 2018’s Black Panther. I remember the film’s release being a cultural event; people talked about it for weeks, the “Wakanda Forever” salute was done by everyone I knew, and it being the first superhero movie to feature a predominantly black cast was inspiring to minorities everywhere. But more groundbreaking than the buzz was the central story of how society has neglected and mistreated black people throughout history, and how change is necessary.

By appealing to a mass audience in the form of a superhero blockbuster, Ryan Coogler got his message across to the entire world. The phenomenon that was Black Panther still echoes through time until today, with people still mourning the loss of the inimitable Chadwick Boseman, a hero to many including myself for pioneering change and peace, and with Black Panther being hailed as one of the best superhero movies ever made (a sentiment that I wholeheartedly agree with). The importance of Black Panther cannot be overstated, and it serves as a massive milestone in black history.

Black representation in film, though it still faces challenges, will continue to improve, and has come a very long way from the days of The Birth of a Nation. Every year, new movies are released that depict perspectives of black lives that are fresh and new for audiences, many of which garner great critical acclaim.

And as long as we support these stories, people around the world will continue to learn about black lives and just how crucial their history is to world history.

World history is our shared history, and by examining black history through film (just like examining any history), we can learn from our past mistakes and open our eyes further to things we may never have been aware of before, educating ourselves in hopes of creating a better future.